In her 2020 book, Untamed, author Glennon Doyle relays an anecdote about a cheetah, who is raised with a dog, trained as a dog, and in sum, is treated as a dog for spectacle. At one point, the cheetah looks to the horizon, beyond the fence that contains it, and this is where Doyle believes that moment exists, where the cheetah knows it is something more than a dog, but does not have such validation from its handlers. Validation, for a cheetah, is in its DNA. But where do we find our validation, as human beings? Certainly, our DNA speaks volumes of our evolution, collectively and specifically. But DNA is merely numbers or figures, much as a balance sheet for the family tree. How do we validate our humanity then? What evidence, may we then demonstrate such intention as that which forms in our double helix? What stories can we glean from something outside of the scientific arena? People surely are measured in ways that exceed numbers, and this is why the modern interpretation of generational wealth is something I wish to percolate on in this blog. What therefore is generational wealth, in the way that we are coming to relate to this term in the modern era? Is it inherited wealth? Inherited illness? Or, is it something more, that anyone can attain, that is not tangible, but intangible and invaluable. I wager it is the latter and shall endeavor to explain why in this short form blog for our women’s history month.

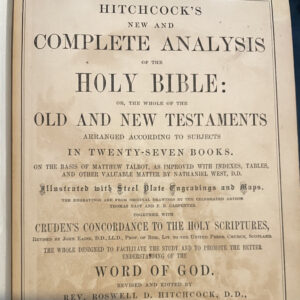

It was not until my mother, who retired abroad with her French husband, my father, that she handed down to me the responsibility, of helming our family narrative. A narrative, I found, which stretches back nearly 600 years, to the court of King Henry VI of England. My earliest known ancestor, remembered for his service as the Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, for which service he earned a knighthood, issued a son who then begat another son and so on, until his name-sake descendant left in the early 17th century as part of the Great Migration of Puritans during the Eleven Years’ Tyranny of King Charles I of England. Puritans were dissatisfied with the Reformation, rejected the Church of England’s tolerance of aspects of Roman Catholicism, advocated greater purity of worship and doctrine, and gave particular focus to reading holy scripture and in particular, the Bible. Put simply, my ancestors arrived in the New World to freely practice their beliefs. And there is where my great grandmother begins our American story, with the arrival of our first American ancestor, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in Sudbury, eventually settling in Marlborough. Their values were reflected in their names: Richard turned to Daniel, then Isaac, and Seth, all biblical names, because these families from the Old World were fleeing tyrannical rule, and establishing an ideal that all men were created equal in the eyes of God, as Christians believe.

This value system of the Christian, Protestant faith is well established in our nation’s history, and reflected in our formative documents, such as the Declaration of Independence. Indeed, the great grandson of our first American ancestor, a captain in the Massachusetts Bay Militia, eventually was elected to the Massachusetts State House, which proposed the Bill of Rights, and ratified the U.S. Constitution in 1788. Faith formed the cornerstone of our Republic, and this faith, along with devotion to education, whether reading holy scriptures, or producing writings, letters, journals, and stories to remark on each others’ adventures, are what I treasure most. This information and knowledge, combined with their artifacts, such as the spoon that my ancestor carried as a Union officer on his march with General Sherman to the sea, razing Atlanta to the ground, stomping out the abomination of slavery, forms the generational wealth that I speak of.